Has this ever happened to you? …

You’re lying in bed and trying to fall asleep when you feel a sudden thunk in your chest. Maybe you sense that your heart is skipping a beat and then giving you a little kick afterwards. This could happen on and off for minutes. What causes these symptoms? The answer is simple: Alien forces have taken over your body. Actually, this is a common and harmless problem called premature ventricular contractions, or PVCs. PVCs, not to be confused with polyvinyl chloride plastic tubing of the same name, are extra heart beats which can feel scary, but in fact, are an important safety mechanism for the heart.

Although I’m a concierge doctor now, I spent the first part of my career as an emergency physician in Seattle at Swedish Medical Center. It was not uncommon for me to see a patient with frequent PVCs coming in quite anxious about these skipped beats and thunks. Even now, at MedNorthwest, it is not unusual for patients to have this issue. Of course, in the primary care setting, I have many more tools and much more time to work up the issue, but what follows is the kind of explanation I give to my patients about the physiology of these PVCs.

Your heart does not want to be fully dependent on that pacemaker. What if it fails? Would the heart just stop completely? No. As it turns out, the heart has many backup cells that can take over if the sinoatrial node stops working. If you shut off the main pacemaker which is keeping the heart beating at, say, 72 times per minute, the heart will start beating at about 40 per minute, owing to a backup pacemaker in the ventricle taking over. As in the Viking ship analogy, if the man at the front falls off, the crew are not going to just sit there and drift in the ocean. Instead, some guy will put his oar in the water and everyone else will join in, and he will set the pace for the boat.

This backup mechanism normally kicks in if the pacemaker, or sinoatrial node, quits functioning. But the heart likes to test this backup system on a regular basis. Imagine you’re one of the guys on the Viking ship who knows that it is your job to start rowing and get everyone else to row along if the man up front falls off. Normally, you’d have to wait until he stopped shouting, “Stroke, stroke, stroke,” to spring into action. But perhaps you want to do a trial run. How? Well, you do a normal stroke as directed by the pacemaker at the front of the ship, then you quickly throw your oar back in the water and pull again, testing that everyone else does the same.

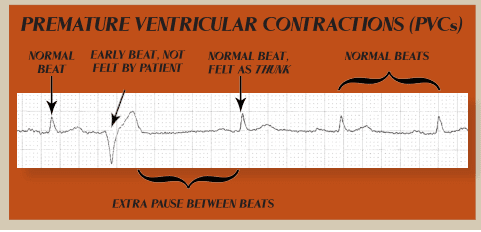

In the case of the heart this is exactly what happens. One of the backup pacemaker cells in the ventricle “fires” early, soon after a regular beat, and the rest of the heart follows. This creates a Premature Ventricular Contraction (PVC).

When all those guys on the Viking ship quickly have to throw their oars back in the water to keep time, they don’t get a full stroke out of it, and the ship does not go as far forward. Likewise, the heart is only half full of blood when the backup pacemaker forces an early beat. If you are lying in bed noting the very subtle beat of your heart, when that early beat comes along there is less blood to be pumped. You might not feel it at all and wrongly think for a moment that your heart has suddenly “stopped.”

The subjective experience is that the heart “skipped” a beat, when in fact, the heart had an extra, early beat which was harder to feel. There was a long pause and a powerful thunk: the normal, compensating, stronger, overfilled beat after the early beat.

Patients who took a

medication called mexiletine to stop

PVCs had worse outcomes.

For folks without heart disease, these PVCs are a normal part of human heart physiology and are of no consequence. In fact, knowing that this system is working should be reassuring. Stress, drinking a lot of coffee, not getting enough sleep, and taking cold medication are all factors that can cause more PVCs. Still, you see them in perfectly healthy eighteen-year-old Air Force recruits as well. Sometimes patients are so distressed by these PVCs that we treat them with medications called beta blockers, such as metoprolol or atenolol, which suppress some of these extra beats. A better treatment is to carefully explain the nature of these extra beats and to offer reassurance to the patient. Often, less coffee and more sleep will help.

For older patients with prior heart attacks, frequent PVCs are a sign of a modestly increased risk of having future heart rhythm problems. One interesting study tried to suppress these extra beats in patients with a prior heart attack, reasoning that if PVCs in patients with significant heart disease were associated with worse outcomes, then suppressing these PVCs should be beneficial. In fact, the opposite was the case. Patients who took a medication (mexiletine) to stop PVCs had worse outcomes.

So, if you’re anxiously lying in bed feeling your heart skip beats and then giving you a little kick in the chest, you should be reassured that this is a perfectly normal backup mechanism that the heart is self-testing. If you are someone with significant heart disease, these extra beats still represent an important safety mechanism, and efforts to suppress them lead to worse outcomes. If your heart is irregular and skipping beats all day long, or is beating quite rapidly and irregularly, you might have something else and should be seen and evaluated.

When I practiced emergency medicine, it was common to see patients complaining of PVCs. In that environment, we just hooked them up to a heart monitor and I could “predict” when their heart would give them a little kick by looking for that early beat. I could then provide reassurance about this problem or make them think I was a psychic, capable of predicting the future, in which case I would then offer stock picking tips to the patient prior to discharge. Now that I’m doing concierge medicine, I have more time to explain the physiology of these premature beats to my patients. Perhaps because Seattle is the coffee capital of the world, we can expect more highly caffeinated patients and more PVCs, but the fact is that caffeine is only one possible factor, and plenty of patients drink a lot of coffee and never notice their PVCs.