Imagine that every pipe in your house started leaking…

Not too good for the house. A similar process is what kills the victims of Ebola virus.

Ebola is one member of a family of incredibly nasty viruses called viral hemorrhagic fevers, which includes hantavirus (found in rodents), Marburg hemorrhagic fever (from monkeys), Lassa fever (also rodents), and others. These viruses are called zoonoses because they normally reside in a non-human host but can infect humans. Ebola is found in primates such as monkeys, gorillas, and chimpanzees, and also in bats. Fortunately for those of us living in the United States, these infections generally occur only in Africa, although an occasional laboratory worker elsewhere has been infected. There has never been a case in North America. Still, understanding how a virus like Ebola can be so deadly is helpful in combating future infections that might strike closer to home.

As with all viral hemorrhagic fevers, Ebola begins like a typical viral infection with fever, body aches, headache, malaise, and so forth. But unlike most viruses, Ebola progresses to a hemorrhagic, or bleeding phase. Hemorrhage means uncontrolled bleeding. It is this bleeding phase that causes death. Patients with Ebola bleed everywhere. They bleed from their eyes, nose, ears, into their kidneys, into the gut, the skin, and most organs. Understanding why this happens will explain what is so deadly about Ebola.

The human circulatory system has two opposite duties. It must remain tightly sealed in certain areas to carry blood around the body, but it also must leak, in a controlled fashion, to allow nutrients, like glucose, water, and vitamins, to get into the various organs. In fact, blood vessels also have to allow large objects like white blood cells to pass through their walls in order to fight infections. In a house, we have solid pipes that deliver water to just a few locations, like the kitchen or bathroom, but in the body, every square inch needs nutrition, so once the arteries branch and become tiny, they must be potentially permeable to white blood cells and all nutrients. At the smallest level of branching, blood cells are called capillaries, and they are so small that red blood cells must squeeze through one at a time.

The human circulatory system has two opposite duties. It must remain tightly sealed in certain areas to carry blood around the body, but it also must leak, in a controlled fashion, to allow nutrients, like glucose, water, and vitamins, to get into the various organs. In fact, blood vessels also have to allow large objects like white blood cells to pass through their walls in order to fight infections. In a house, we have solid pipes that deliver water to just a few locations, like the kitchen or bathroom, but in the body, every square inch needs nutrition, so once the arteries branch and become tiny, they must be potentially permeable to white blood cells and all nutrients. At the smallest level of branching, blood cells are called capillaries, and they are so small that red blood cells must squeeze through one at a time.

When we’re sick, the body releases chemicals that make capillaries, small arteries, and tiny veins more leaky. This facilitates the movement of antibodies and white blood cells into infected tissues, which is normally a good thing, but too much leakage causes excessive amounts of water and proteins to leave the circulation and enter the tissues. The result is low blood pressure within the circulation (because Elvis has left the building) and swelling (because he is now outside the circulatory system and in the skin, fat, liver, etc).

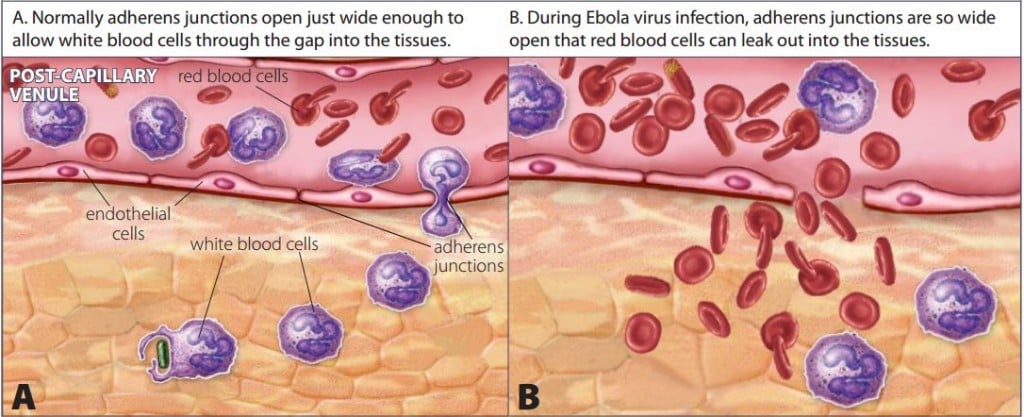

Ebola virus can attack the liver and certain types of white blood cells, but the most troublesome target is a specific cell type in the body called endothelial cells. These cells line all our blood vessels. That is their job, to be a lining, like the horrific paneling in my parents’ family room in Los Angeles, or the green checkered contact paper that lined the kitchen shelves in my apartment in medical school. Although endothelial cells line the entire circulatory system, Ebola mainly targets specific endothelial cells in the tiny veins that collect blood from the capillaries. These tiny veins are called post-capillary venules. In many of these venules, there is a small gap between each endothelial lining cell, just as when you lay down tile, there is a gap between each tile. Into the gap, a home builder places mortar. In the body, different types of gaps are more or less permeable to nutrients and white blood cells. One type of gap is called an adherens junction. The adherens junctions are the site where white blood cells can attach and then squeeze through, so these junctions between cells are more like sliding doors.

Ebola virus has a protein in its membrane called glycoprotein GP1,2, which causes the endothelial cells to throw these adherens junctions wide open. Normally, they would open just enough to let antibodies and the occasional white blood cell squeeze through, but now, after the viral attack, the junctions are so open and permeable that red blood cells and all sorts of fluid leak out into the tissues. This is how Ebola causes bleeding and death. The human circulatory system has two opposite duties. It must remain tightly sealed in certain areas to carry blood around the body, but it also must leak, in a controlled fashion, to allow nutrients, like glucose, water, and vitamins, to get into the various organs. In fact, blood vessels also have to allow large objects like white blood cells to pass through their walls in order to fight infections. In a house, we have solid pipes that deliver water to just a few locations, like the kitchen or bathroom, but in the body, every square inch needs nutrition, so once the arteries branch and become tiny, they must be potentially permeable to white blood cells and all nutrients. At the smallest level of branching, blood cells are called capillaries, and they are so small that red blood cells must squeeze through one at a time.

When we’re sick, the body releases chemicals that make capillaries, small arteries, and tiny veins more leaky. This facilitates the movement of antibodies and white blood cells into infected tissues, which is normally a good thing, but too much leakage causes excessive amounts of water and proteins to leave the circulation and enter the tissues. The result is low blood pressure within the circulation (because Elvis has left the building) and swelling (because he is now outside the circulatory system and in the skin, fat, liver, etc).

Ebola virus can attack the liver and certain types of white blood cells, but the most troublesome target is a specific cell type in the body called endothelial cells. These cells line all our blood vessels. That is their job, to be a lining, like the horrific paneling in my parents’ family room in Los Angeles, or the green checkered contact paper that lined the kitchen shelves in my apartment in medical school. Although endothelial cells line the entire circulatory system, Ebola mainly targets specific endothelial cells in the tiny veins that collect blood from the capillaries. These tiny veins are called post-capillary venules. In many of these venules, there is a small gap between each endothelial lining cell, just as when you lay down tile, there is a gap between each tile. Into the gap, a home builder places mortar. In the body, different types of gaps are more or less permeable to nutrients and white blood cells. One type of gap is called an adherens junction. The adherens junctions are the site where white blood cells can attach and then squeeze through, so these junctions between cells are more like sliding doors.

Ebola virus has a protein in its membrane called glycoprotein GP1,2, which causes the endothelial cells to throw these adherens junctions wide open. Normally, they would open just enough to let antibodies and the occasional white blood cell squeeze through, but now, after the viral attack, the junctions are so open and permeable that red blood cells and all sorts of fluid leak out into the tissues. This is how Ebola causes bleeding and death.

What makes the Ebola virus even more scary

is that it is highly contagious.

The victim has blood coming from every orifice in the body and that blood is full of Ebola virus particles. Saliva is also contagious. Just getting the virus on intact skin is enough to transmit it. In the parts of the world where Ebola occurs, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaїre), the entire annual per person expenditure on health care is $15 (as opposed to $6,000 in the United States). $15 is not enough to buy a single protective suit against Ebola. Health care workers have frequently died from Ebola after caring for a victim, as have villagers preparing bodies for burial. There is even a case of sexual transmission from a rare individual who recovered. The 10% of patients who don’t die are capable of transmitting the disease for weeks afterwards through their body fluids.

Research into a vaccine or other treatment on Ebola is limited by the extraordinary safety precautions needed when handling the virus. Also, funding is sparse compared to much more common conditions, like Alzheimer’s or heart disease. Still, if an easily transmitted viral hemorrhagic fever like Ebola were to become established in the United States, the potential risk to public health is enormous.