Of all the diseases I commonly see in primary care …

none is more likely to be improperly treated than bronchitis. What is bronchitis and why do physicians and patients often approach this disease incorrectly?

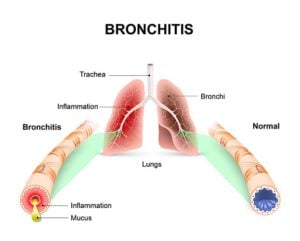

Bronchitis is divided into two versions. Acute bronchitis is an infectious process where the patient is ill and then recovers fully. Chronic bronchitis, on the other hand, is a non-infectious process, usually seen in smokers, which goes on for years. The topic of this article is acute bronchitis.

To understand bronchitis, we should first examine the word bronch + itis. The suffix –itis means “inflammation of.” If you get a splinter in your finger and it is red, warm and tender, that is the inflammatory response. This response is driven by the immune system which sends out white blood cells and increases blood flow to fight off an infection or other disorder. Doctors usually stick a Greek or Latin word in front of –itis to make it a disease. Dermatitis, for example, means inflammation of the skin because derma means skin in Greek. Gastritis means inflammation of the stomach. Tonsillitis is inflammation of the tonsils, and so forth.

By contrast, the suffix –opathy means “disease of” and –osis can mean “disease of” or “too many.” When twelfth graders quit doing any work in the second semester after they have already been accepted to college, some people call this senioritis, but this is incorrect since there is no inflammatory response present. Seniorosis or senioropathy would be more correct terms.

We all know the important function of the lungs. This is where oxygen is delivered into red blood cells and carbon dioxide is removed. In order for this exchange to take place, we need to get a red blood cell as close to the air of the outside world as possible. We suck air from the room into our lungs and place a bit of it right next to flowing blood with only a very thin wall between the two. The wall, called the respiratory membrane, is so thin that if you stacked 3,000 of them on top of each other, it would be as thick as a penny.

This pocket of air and the tiny arteries and veins around it are held together in a structure called the alveolus (Al-VEE-oh-lus). Some people think of it like a bunch of grapes on the vine. We typically have 700,000,000 alveoli (pleural, Al-VEE-oh-lie) in our lungs. When bacteria or viruses attack the alveoli, the body sends in white blood cells to fight the infection. The respiratory membrane leaks, causing the alveoli fill up with fluid and air can no longer enter. This is pneumonia.

You might imagine an alien species where the lung tissue is on the outside of the body. Perhaps a mass of these alveoli would sit on an alien’s back. As the aliens walked down the street, or glided by in their hovercraft, air molecules would flow past and exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide. But because these structures are so delicate and because we need such a huge surface area, in humans all these alveoli are clustered together and protected inside the chest to make up the lungs.

How do we get air from the outside world into the alveoli? We do so by breathing, of course. In order for air to travel one or two feet from our mouths to the alveoli, our lungs have a massive branching network of passageways. We call the set of branching hollow tubes that form a path for air to reach the lungs the airways. The first part of the airway is the tube encountered just below the back of the throat, called the trachea. You can feel your own trachea in the front of your neck. It is obvious, firm, and lined with cartilage.

Just below your neck, the trachea splits into right and left passageways. As Yogi Berra once said, when you come to a fork in the road, take it. These two passageways send air into the right and left lungs and are called the right mainstem bronchus and left mainstem bronchus, respectively. Like the branches of a tree, the bronchi continue to divide and narrow throughout the lungs. They undergo about 16 divisions, getting smaller each time, until we start to encounter alveoli. There are another four or five branches until we reach the end where the majority of the alveoli are located.

When the bronchi become very small, less than about 1/8 inch, they no longer have any cartilage lining them and we call them bronchioles. In kids, inflammation here is called bronchiolitis and is a common cause of an acute respiratory illness with wheezing in small children.

So the sequence is from mouth to the trachea, to the right or left mainstem bronchi, to the rest of the bronchi down to the bronchioles and finally to the alveoli. If our analogy is to a tree, this one is upside down, where the trachea is the trunk and the branches divide and narrow and the alveoli are leaves. Another analogy is to highways and roads where Interstate 5 is the trachea and the exit off of Madison would be a bronchus and as the main road divides and narrows to smaller and smaller side streets you enter the bronchioles until finally you pull into a driveway and the house is an alveolus.

I mentioned that if the alveoli are infected we call it pneumonia; if the very tiny airways, the bronchioles, are infected, then this is bronchiolitis. The trachea can become infected as well, causing tracheitis. But what if the bronchi—these large, cartilage lined tubes which provide a passageway for air into the lungs—are infected? Well, this is bronchitis.

A key question to ask is this: What kind of organisms infect the bronchi? Obviously, the bronchi are exposed to outside air so many bacteria and viruses pass through on their way to the alveoli. It is helpful to remember that different organisms infect different parts of the body. For example, the E. coli bacteria lives in the colon and commonly infects the bladder, but E. coli almost never infects the skin. The herpes virus infects the skin but rarely infects the liver.

It turns out that about 95% of bronchitis is caused by viruses. Bacteria almost never infect the bronchi and when they do, antibiotics still don’t help patients get better any sooner. Patients wrongly think that if their sputum is yellow or green, this means they have a bacterial infection. This is totally incorrect. In many studies, 60–90% of patients with obvious cases of bronchitis are improperly given antibiotics. This single disease accounts for more inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions than any other. Virtually all acute bronchitis is viral and should not be treated with antibiotics, regardless of the color of the sputum, the duration of the illness, the presence of “burning” in the chest, and so forth. However, don’t take my word for it. Just Google “bronchitis antibiotics.” The first twenty hits (I got bored after that) all say the same thing I am telling you right here: it is wrong to take antibiotics for bronchitis.

Certain bacteria, such as mycoplasma and chlamydia (the pneumonia version not the STD version) can cause bronchitis, but antibiotics do not help patients get better any faster. Whooping cough is a bronchitis caused by bacteria, but except in very rare circumstances, it is impossible to distinguish early whooping cough from a cold. Both present with a runny nose and perhaps a mild cough. By the time a true bronchitis picture emerges in whooping cough, antibiotics won’t shorten the duration of illness, although they may reduce spread to others.

There are no well-conducted randomized studies that have ever been done in the history of medicine showing a significant benefit to patients by taking antibiotics for bronchitis, but many studies have been done showing antibiotics to be of no value.

The key diagnostic dilemma in most cases is distinguishing bronchitis, almost always viral, from pneumonia, which can be viral or bacterial. Bronchitis does not show up on chest x-rays but pneumonia often does. Patients with pneumonia tend to have fever, lower oxygen levels, faster respiratory rates, and their lungs may sound abnormal on listening with a stethoscope. Unfortunately, no test is 100% perfect. Sometimes, pneumonia is not apparent on a chest x-ray. A typical patient with bronchitis has a normal oxygen level, clear lungs, no fever, a normal respiratory rate and a normal chest x-ray. This individual should not take antibiotics. Some would argue that the x-ray is not even necessary in a well-appearing patient with these findings. In elderly, chronically ill, or otherwise compromised patients, it is acceptable to prescribe antibiotics when there is a question of early pneumonia versus bronchitis, but equally appropriate to wait 24 hours to see if the condition progresses. Patients with pneumonia should be treated with antibiotics, although many cases of pneumonia are viral and milder cases of pneumonia often go untreated and patients will do just fine.

The next problem with bronchitis is that the most troubling symptom, cough, can’t really be treated very effectively. All over-the-counter cough medicines are pretty much worthless. The narcotic-containing prescription medications only reduce cough because patients get stoned and sleepy. They don’t actually directly impact cough. You’re better off just taking an Ambien. I do find that cough drops such as Halls can be helpful for some folks.

The final problem in treating patients with bronchitis is that people fail to understand the impact and seriousness of viral infections generally. There is a popular notion, wholly incorrect, that somehow bacterial infections are more serious than viruses. Well, if we consider that smallpox, herpes encephalitis, SARS, AIDS, and Ebola are all viruses, it should be clear that viral infections can be plenty serious. In the case of viral bronchitis, there is widespread destruction of the cells lining the respiratory tree. It can take weeks for these tissues to recover. If you were to have a bronchoscopy performed during acute bronchitis you would see that your airways are lined with pus, mucous, and other junk. On microscopic examination, you’d see millions of white blood cells fighting this infection. If you went to the level of an electron microscope, you’d see millions of dead respiratory lining cells and billions of virus particles as well.

About 95% of bronchitis is caused by viruses and

should not be treated with antibiotics.

Even when bacteria infect the bronchi,

antibiotics still don’t help.

Some patients feel they are not being taken seriously if they don’t receive an antibiotic, and many physicians are unable to take the time to explain the situation, even though one study showed that such an explanation only added one minute to the patient visit. In addition, doctors don’t want to risk having a dissatisfied patient. Because a few patients with bronchitis will later develop pneumonia, some physicians prescribe antibiotics to patients with obvious cases of bronchitis so that if pneumonia does develop later on, it looks better. At least the doctor had the patient on antibiotics, for cryin’ out loud! But the fact is that giving antibiotics to patients with viral bronchitis probably does not prevent pneumonia. The only study to suggest a slight benefit was not a well-conducted randomized trial and has many methodological flaws. The most generous interpretation of that study suggests that treating 100 patients with antibiotics for bronchitis prevents one case of pneumonia, but the complication rate from 100 antibiotic prescriptions is obviously higher. A less charitable interpretation of this study is that giving everyone who appears to have bronchitis antibiotics will occasionally treat a pneumonia.

All expert consensus opinions recommend avoiding antibiotics for bronchitis, although some leave it as an option for the frail elderly. Note that the issue here is the subsequent development of pneumonia later on. No study has ever shown that antibiotics help the illness in question—acute bronchitis. The better strategy is to give antibiotics to older patients where there is a serious possibility of pneumonia and to withhold them when it is clearly a viral infection.

To give you some idea about how deeply ingrained the habit is of giving antibiotics unnecessarily for bronchitis, consider this study of a large integrated health care network on the East coast published in 2012. The Geisinger Health system told its doctors that prescribing antibiotics for acute bronchitis would be a negative quality mark against them. Sure enough, prescriptions for “acute bronchitis” declined from around 77% to 27% over three years. But what really happened is that doctors changed the diagnosis from “acute bronchitis” to “bronchitis, not specified as acute or chronic,” a diagnosis for which there is no black mark against them when giving antibiotics. The actual antibiotic prescribing pattern never changed at all.

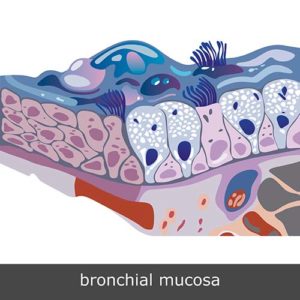

These are the microscopic hairs called cilia that line the airway and help protect the lungs. After bronchitis, many of these hair cells die and take weeks to grow back.

Another frustrating aspect of bronchitis is that long after the infection has resolved, patients may continue to cough. It is common to cough for three weeks after an episode of bronchitis and even six weeks of coughing is not rare. When the viruses which cause bronchitis attack the bronchi, they often invade a specialized type of cell lining the airway. These cells have little microscopic hairs on them and constantly wave in an upward direction. When we inhale dust particles, they are caught in the mucous lining the airway and then swept back up into the throat by these hairs and later swallowed. The organized action of these millions of cells is called the mucociliary elevator. After an episode of bronchitis, many of these hair cells are dead and it can take weeks for them to grow back. In the meantime, the only way the lungs can protect themselves and clear out debris is by repeated, sometimes dry, annoying, persistent coughing.

When an ill patient seeks out care because of cough, he or she should ask the doctor to try and distinguish viral bronchitis from bacterial pneumonia and should decline to take antibiotics for bronchitis except in very rare circumstances. Cough drops can be worthwhile, but otherwise patients should generally avoid cough medications because they are not helpful.

Bronchitis is a difficult, vexing problem in health care. Patients have come to expect that physicians have a treatment every illness. Bronchitis has no effective treatment. The goal of a physician in this setting is to distinguish bronchitis from pneumonia. This alone does not satisfy many patients. The result is massive overprescribing of antibiotics for a self-limited, self-curing viral condition. You can be your own best advocate by asking the doctor, “Are you just prescribing these pills to make me happy? If it were you, would you really take antibiotics for this condition?”