For over one hundred years, doctors and patients …

have used the term tendonitis to indicate pain in or near a tendon. Tennis elbow, jumper’s knee, and pain in the tendons of the shoulder, wrist, and heel are examples of this common problem. Recent research has led to a revolution in our understanding of tendonitis. To sort out the new thinking about painful tendons, we first need to figure out what a tendon is and why the term tendonitis is incorrect. Then we can evaluate the merits of some newer treatment approaches.

So what is the point of having tendons anyway? Tendons connect muscles to bone. Muscles are amazing structures that have two main functions: The first is to impress women, and the second is to contract. All movement in the body occurs because a muscle shortens. Sure muscles can relax and stretch back out, but they can’t push themselves out actively; they only contract actively. If you wish to bend your elbow, the big, beefy biceps muscle contracts. Since it is attached to your shoulder at the top and the lower arm at the bottom, when it shortens the elbow swings inward, just like a hinge. Now to straighten your elbow back out, the biceps muscle does not push or stretch out. Instead, it just relaxes and the muscle on the other side of your upper arm, called the triceps, shortens. This straightens the elbow.

So now we have some idea about the tendon part of the term tendonitis. But what about –itis? As I’ve discussed in other articles, laypersons use the suffix –itis to mean “disease of.” “Bill got into Notre Dame and now he is not studying and just goofing off. He has senioritis.” Or, “Jimmy said he had a tummy ache on Monday morning, but I think it was just school-itis.” But doctors use the suffix –itis to mean “inflammation of” not “disease of.” So if a structure in the body is red, sore, tender, and warm, or if there are a lot of white blood cells around and increased blood flow, we would use that suffix, as in hepatitis to mean inflammation of the liver, colitis to mean inflammation of the colon, gingivitis for inflammation of the gums, and so forth.

Doctors use the suffix –opathy to mean “disease of.” Also, we sometimes use the suffix –osis for the same thing. Cardiomyopathy means a disease of the heart muscle; myelopathy is a disorder of the spinal cord.

When we look at these painful tendons under the microscope, we see that they are abnormal, but there is no inflammatory process underway. Occasionally, I do see a patient who really has a tendonitis, in that the skin over the tendon is red and warm and that tendon surely is inflamed, but this is unusual. Typically, I see a patient who has pain in a tendon which is worse with use and better with rest, tennis elbow is a prime example.

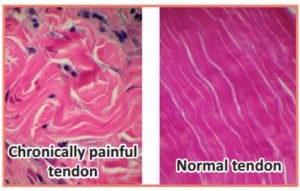

Well, speaking as a scientist, we have to ask, what in tarnation is going on in that them thar tendons? If you look at a painful tendon side-by-side with a normal tendon, you see a striking difference. The healthy tendon is glistening white, and under the microscope, its elements are all lined up in nearly perfect parallel lines. A chronically painful tendon looks more grey in color and the collagen fibers are broken and disorganized. Additionally, there is some extra gunk, called mucoid ground substance. But you don’t see lots of white blood cells or other signs of typical inflammation. Pathologists use the term tendinosis to describe this appearance under the microscope and some physicians use the same term to describe people with painful tendons that get worse with use and improve with rest.

Tendinopathies are incredibly common. They account for 7% of all outpatient visits to a physician, and they are stubborn little b$%#$!*, too. It is not unusual to have pain in or around a tendon, worse with use, better with rest, that goes on for a year. Patients are unable to play tennis, work using their hands, run, and so forth. Sometimes, what we call bursitis, an inflammatory condition of a bursa, is really a tendinopathy involving a nearby tendon. The gluteal tendon can be affected, causing butt or hip pain. The shoulder tendons get involved and although sometimes doctors may call it arthritis or bursitis, in many cases the actual cause is a tendinopathy. It is often not possible to make an exact diagnosis from the physical exam, and even imaging studies like MRI or ultrasound of the t

For the past five decades, doctors of all stripes have treated tendinopathies with injections of cortisone. Family doctors, orthopedic surgeons, rheumatologists, rehab specialists, internists, hand surgeons, sports medicine doctors, well, you name it, all have shot doses of cortisone around painful tendons, and there are millions of patients who have experienced dramatic relief with these treatments. The trouble is that the underlying process is not one of inflammation, it is one of degeneration, and cortisone shouldn’t, in theory, be the correct approach.

A study from Australia reported in the February 6, 2013 Journal of the American Medical Association shows the problem, at least where tennis elbow is concerned. In that study, 163 patients were randomly assigned to get a steroid shot or a placebo (salt water) shot for tennis elbow. A group also got physical therapy in addition to the shot, but physical therapy did not have much effect on the outcome. No surprise that after four weeks, 71% of the folks who got a steroid shot were either completely better or almost all better as compared to only 10% who got the placebo shot. There was no fooling these folks. In fact, I suspect that if they had checked with their study subjects after just three days instead of four weeks, they would have already found a big difference between the two groups.

But what these researchers did was come back one year later and see how everyone was doing. After one year, the placebo group was actually doing slightly better and the recurrence rate was higher in those patients who received steroids; 83% fully recovered in the group who received steroids versus 96% in those who got placebo. One possible explanation is that because cortisone was so effective as a pain reliever, patients went right back to playing tennis or doing whatever was causing their tennis elbow in the first place and this accounts for the worse outcome. Another possibility is that the cortisone itself is somehow harmful to the affected tendon. I think it is more likely that rapid return to full activity caused the worse long-term outcome.

The most widely promoted physical therapy

for tendinopathy is

called eccentric exercise.

Doctors are not going to abandon 50 years of giving cortisone shots based on a single study with 163 patients, and if you’ve ever been in significant pain from this disorder you know how disruptive it can be. But it does force us to rethink our approach to some of these tendinopathies.

The most common approach is activity modification. Play less tennis or try another sport for a while. Use a power screwdriver on the job. This should be the first step whenever possible. If that is unsuccessful, patients might want to try therapeutic exercises.

The most widely promoted physical therapy for tendinopathy is called eccentric exercise. This involves stretching of the involved tendon slowly under force. If it is your Achilles which hurts, you stand on the edge of a stair on your tippy toes and slowly lower down until your heel is below the level of the step. For tennis elbow, a short, twisting bar called a “Flex Rod,” $12 on Amazon, can be used to slowly flex the wrist under different levels of tension.

The general approach, which is sometimes effective, is to slowly stretch whatever tendon hurts under force, using your own muscular contraction.

There are some non-cortisone medications for treating tendon pain. Will they have the same problem that we’ve seen with cortisone for tennis elbow—relieving pain in the short term but making matters slightly worse in the long term? No one knows.

One such approach is topical nitroglycerin. You take a nitroglycerin patch and place it over the area of pain. In some studies, a higher dose patch was cut into quarters. The evidence is mixed and there is no one year or longer data on outcomes.

Another approach is to take NSAIDs like Motrin or even use them topically at the site of pain. Pain is improved, but there is no long term benefit in terms of the underlying problem. Some doctors prescribe “round-the-clock” anti-inflammatories for tendon pain, but there is no science to support this approach and these drugs have risks.

Some physicians have tried injection a patient’s own blood, or a special preparation of plasma and platelets, into the region of the affected tendon. There is little good science to support these approaches, but they have been tried. Another approach is to inject Botox at the site of the tendon. This has not really panned out. Sometimes, patients will end up with tendon surgery to relieve their pain. This is most common for tennis elbow.

Tendinopathies are common, vexing, and frustrating for patients. The first step in treatment is modifying the activity which is causing tendon pain. For decades, the preferred approach after activity modification has been to inject cortisone around the affected tendon. Although this procedure is highly effective at relieving pain, it may slightly reduce the chance for a full recovery by one year. Other approaches are under development. Among these, eccentric exercises have the most promise, but there is no one perfect solution for all cases of this disorder.