We’ve all seen the horror movie where …

we think the bad guy has been killed off, but he is really hiding in the basement ready to attack the girls at the sorority as soon as the cops wrap things up and head home. This is just how shingles works.

Shingles is a skin rash which commonly affects adults over 50. The rash is red, splotchy, and sometimes appears with small blisters. It usually occurs only on one side of the body in a narrow patch along the trunk, on part of an arm, or on an area of the face. The shingles rash will resolve with or without treatment in a couple of weeks. However, the most feared complication is persistent pain in the area of the rash, even after the rash has cleared up.

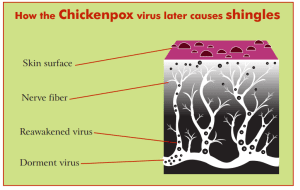

Shingles is caused by the varicella zoster virus, exactly the same virus which causes chickenpox in kids. Zoster is just the medical term for shingles, and varicella is chickenpox. It turns out that when you’re a kid and get chickenpox, the varicella zoster virus is never cleared totally out of your body. Like that creepy bad guy who was hiding in the basement waiting for the cops to go home, the chickenpox virus hides out in the nerves in your spine waiting for a weakness in your immune system. In general, your body’s immune system keeps that virus in check, but after many decades, your immune defenses against chickenpox begin to decline. When that happens, the virus migrates along the course of your nerves from the spine to the skin where it breaks out into a rash that looks like a localized case of chickenpox gone awfully wrong. Compared to regular chickenpox, the zoster rash has larger red blotches and fewer tiny blisters, and unlike regular chickenpox, it can hurt—a lot.

If the rash heals up, but pain persists, we call it postherpetic neuralgia. Post means after, and neuralgia means pain from an injury to a nerve. (If you break your arm, the nerve just carries a pain message about the arm, but if you crush a nerve, it carries a pain message about itself, and that pain is usually more severe and harder to treat.) But what about the word herpetic in postherpetic neuralgia?

It turns out that chickenpox is in a family of viruses with similar biological behavior. They are all famous for “hiding out” in the body. Cold sores or herpes simplex type I, genital herpes or herpes simplex II, chickenpox, even the virus which causes mononucleosis, as well as a few others, are all “herpes” viruses. Therefore, if a 5 year old boy were brought into my office by his anxious parents with typical chickenpox, it would be scientifically correct for me to tell them that he has a total body herpes infection.

In general, the risk for postherpetic neuralgia rises with age. Patients over the age of 80 have a 25% chance of getting it if they have a case of shingles. Patients aged 60-70 have about a 7% chance. Below age 50, it is very rare.

I treat most patients who get shingles with three different drugs to speed healing and decrease the risk of postherpetic neuralgia. The first is an antiviral drug, like Valtrex or acyclovir, which prevents the virus from making copies of itself. The second is prednisone, which helps reduce inflammation of the nerve. The third is a drug like nortriptyline, which quiets down nerves and reduces pain. In randomized trials, Valtrex and prednisone help speed healing of the rash and reduce short-term pain, but it is unclear if they really prevent postherpetic neuralgia. Nortriptyline may help prevent postherpetic neuralgia, but we don’t have many studies with this particular medication.

Folks usually have only one episode of shingles in their lifetime. The recurrence of the varicella zoster virus triggers a large immune response which is then able to keep the virus in check for the rest of your life.

In the 1990s, a vaccine against chickenpox was introduced. Eventually, there will be a generation of kids coming along, most of whom don’t get chickenpox. The vaccine is about 90% effective. Kids who receive the varicella immunization should never get shingles either. One concern, however, is that after 50 or 60 years, vaccine-created immunity to chickenpox might decline, leaving older adults at risk for chickenpox but not shingles. In children, chickenpox is usually a fairly mild illness, but it can be fatal in adults. Any adult who is not certain he or she had chickenpox during childhood should have antibodies drawn, and if negative, get two doses of the kids’ chickenpox vaccine. The only death I’ve ever seen from chickenpox was in a 38-year-old man, and it was not a pretty sight, let me tell you.

Out of 14,000 patients who received Shingrix in a research study, there were only 4 cases of post-herpetic neuralgia.

Since shingles represents the recurrence of chickenpox when immunity declines after many decades, it occurred to scientists and to the pharmaceutical companies to try and develop a vaccine which would boost immunity to chickenpox and prevent shingles. Instead of an outbreak of shingles serving as your “booster shot” for chickenpox immunity, why not just give patients a real booster shot? This is the strategy behind the shingles vaccine.

Zostavax was the first vaccine introduced for shingles prevention and was later replaced by Shingrix, which is the currently used version. It’s a two shot series, given at time 0 and repeated 2-6 months later. The vaccine can be given at age 50, or age 18 for patients who are immunocompromised. I find that patients under 70 typically get sick for 24-48 hours with this vaccine, complaining of body aches and feeling like the flu. This is less common in older patients. That said, being ill for a day or so is way better than having years of nerve pain from shingles.

No one knows how long the vaccine will last or if a booster will be necessary. Right now, no vaccine doses beyond the first two are recommended. The vaccine is 90% or better in effectiveness against both shingles and the feared complication of post-herpetic neuralgia.

If you’ve never had shingles, and in particular if you’ve never had postherpetic neuralgia, then this shot just seems like another hassle, something you need to do and don’t want to bother with. If a close friend or family member has had postherpetic neuralgia, you will definitely, oh most definitely, be wanting this vaccine. There can be some vaccine “noise” with widespread recommendations for things like annual flu shots, the RSV vaccine, a million COVID boosters, but don’t let that noise drown out the message that this is a life changing vaccine to prevent years of agonizing nerve pain and well worth doing.